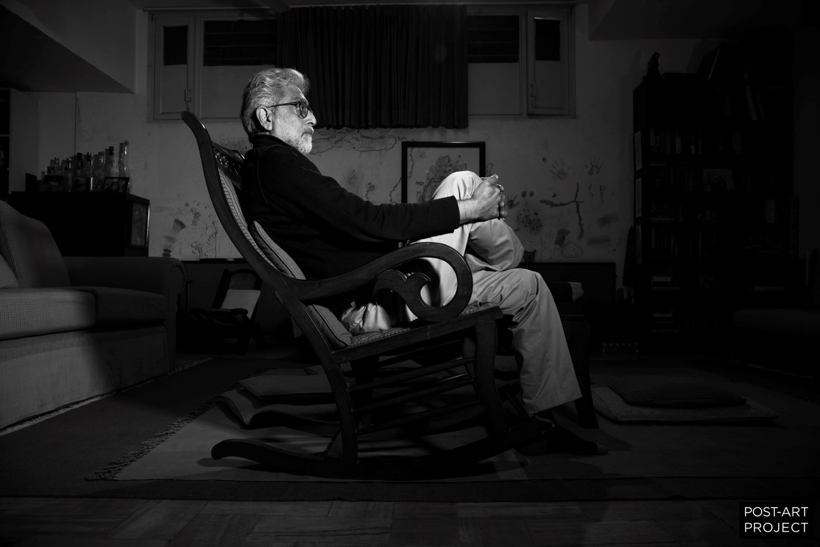

They are homeless; most of them come from rural India in search of job or are displaced from their native place for one reason or the other. They come looking for a dream, but end up on the streets.

New Delhi: It’s been three years since Parvez came to Delhi. Life was not easy for him in Bada Mohalla, Meerut, in Western UP, after his parents passed away. Left to his fate, Parvez decided to board a train to Delhi, a city as chaotic as his own personal life. Since then, he would earn a bit here and there, and roam around the city’s lanes and by lanes — homeless, sleepless, rootless, faceless, often solitary, and hungry.

As usual, Parvez was drunk on cheap liquor on a freezing Friday night in December. He walked towards the Kashmiri Gate flyover. He found a place in a quiet corner below the flyover. He was exhausted after the day’s wandering; so he just went to sleep on an empty stomach. It was another inevitable, sad night of homeless despair.

The ‘Safe Approach Rescue Team’ of volunteers was patrolling in the night around the area. They found Parvez and took him to the porta cabin night shelter in the neighbourhood. “He was shivering in the cold. I gave him my own blanket to cover,” said Safe Approach volunteer Ajith Kumar.“I used to sleep around mandirs and gurudwaras,” said Parvez, 29, speaking to KRC Times. “Often, I used to sleep on pavements and street corners. It’s so comfortable here in the night shelter. Now I have my own mattress. I have got a blanket, a bed-sheet, a pillow. They provide us food and water. I got a new pair of chappals, pyjama and sweatshirt,” he said, while a dubbed Tamil movie is being screened on the LCD screen at the night shelter.

Kamal Khan, 55, has been living in the porta cabin in Kashmere Gate since the last two years. He fought with his nephew, left his home in Seemapuri in East Delhi and came to the night shelter. “Here, I am happy. I am peaceful. Nobody interferes with my life. I am getting food on time and a place to sleep,” said Khan, smoking his Pataka beedi.

As evening sets, the Sadar Thana Road in North Delhi is bustling with people, traffic, rickshaws, hand-carts and clueless cows in the midst of it all. After the first left turn, approximately 500 metres ahead, on the right stands a four-storey yellow building – the Motia Khan night shelter.

Thesound ofthe famous Nashik dhol reverberates in the background. Three kids play the dhol and a group of children dance to the tune. On the right side in the courtyard Nashik dhols are lying on the ground — waiting. A group of women are busy preparing food in the temporary kitchen. Five green steel cots are aligned parallel to the courtyard. Residents are having a chat over steaming hot tea while the children play around, filling in the space. A girl sits in a corner, grooming her little sister, braiding her hair. The people next to the fire near the tarpaulin are into a petty fight regarding their daily share from the dhol band.

“Only single males are allowed here. Drinking and smoking is strictly prohibited. Most of us live with families. We don’t entertain a person without a proper identity card,” said Ishu, who has been living at the night shelter with his family since 2007.

The hall in the left corner of the third floor is reserved as the night shelter. The rest of the rooms are occupied by families — mostly dhol players from Maharashtra and Karnataka. Pictures of numerous gods — from Buddha to Shiva — occupy the right corner of the wall.

“We want to create an impression that they are living inside a sacred space. When they enter the room and see these pictures, they respect the space; they don’t create any problems. It’s a psychological trick,” said caretaker Ashutosh Tiwari, winking.

The caretaker walked with him towards the trunk. He opened the lid and took out the blankets and mats. The old man walked towards a corner. He spread the mat, made a mattress out of the blankets, covered his body with blankets, and went to sleep.

The family rooms are also similar to the night shelter. A big hall has been converted into four homes. A bed-sheet acts as the wall between homes. On the left corner of the room lie the dholaks, utensils and clothes. A Bollywood action movie is playing on the TV screen. Two children, sitting on a rajai, are glued to the TV screen. A baby is screaming in the next room. The mother is trying her best to make the baby sleep.

Old Hindi songs are playing in the third room. Black and white garlanded photos of a ‘dadaji’, with an interesting moustache, and gods, are hanging on the top corner. “He uses drugs a lot; every day he is coming home with a dull face,” a mother complains about her 10-year old boy to the caretaker. The caretaker scolded the boy and then cajoled him to stop taking drugs. The boy seemed totally spaced out.

There are around 203 night shelters all around Delhi.

Of these, there are 76 regional centre buildings, 112 portable cabins and 15 tents. About 38 night shelter homes are functioning at Kashmere Gate. The night shelters can host a total of 17,170 people. On the night of December 14, 8,466 people had slept at the night shelters. A study conducted by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) and other NGOs in 2011 has found that there are at least 2,46, 800 homeless people in Delhi.

At least, 463 unidentified bodies were found by police from the streets of Delhi last year. Most of them were homeless.

Most of the homeless come from rural parts of India who are jobless, rootless or displaced from their homes, communities and villages. They come looking for a dream, but end up on the streets. The lucky ones, many of them daily wagers, find the night shelters. Others are ravaged and ruined by life’s relentless despair and a big city’s impersonal and cruel conduct, unable to cope with their own damaged minds and emaciated bodies, and a life without anchors or hope.

As the winter becomes frozen, relentless and deathly, many of them die in their sleep, often hungry, drugged and intoxicated. As is the ritual for many decades, their dead bodies are recorded by the police as people with no identities, families, professions, names or address. Nameless and homeless, they once again vanish into the blue.