The main reason for the renovation and expansion of the road was to create an additional route for the supply of goods to the British Army garrisons and depots in Imphal. This route was also to help assist the returning British allied troops who were returning to India after the fall of Burma to the Japanese

Yumnam Rajeshwor Singh

Yumnam Rajeshwor Singh

Introduction

Tongjei Maril was one of those trek routes that connected the erstwhile kingdom of Manipur with other princely states where transportation was based on horseback. The route was also used for commercial activities with other kingdom or nations and many Kings of Manipur depended on this particular track. In between July and September of 1942, Lieutenant Colonel G P Chapman along with 150 officers and men from the 82 Anti-Tank regiment of the Royal Artillery, with assistance from the local people renovated and widen the existing path as a road on which Jeep vehicle could pass through easily. Those officers and men from the 82 Anti-Tank Regiment were also called “Chapforce”.

During early 1942, when Burma was captured by the Japanese, Manipur saw a large exodus of Indian, British and other nationals passing through Imphal. They either took the Imphal- Dimapur Road or this bridle path to Silchar by foot. The Imphal-Dimapur Road was quite immature and a shifty thing at the best of times. It traverses the sides of mountains, ridges and saddles, ascending to some 6000 feet at one part, and always dangerous. The drop feet at one side or the other (the khud), at times, was simply colossal, and the whole distance of 135 miles was littered with smashed-up vehicles, some down hundreds of feet. And in June 1942, it was littered with bodies-the death and dying of the refugees who swarmed by in thousands, and died of cholera, dysentery and exhaustion in hundreds. Every day more vehicles dived over the khud, and men and friends were killed or hurt. The road started to collapse with monotonous regularity. The combination of torrential rains and heavy military traffic was its death knell. The Imphal-Dimapur road was closed for weeks at a time, then open for a few days, only to be closed again. Then a hill would tumble down on it, and it really closed for another week or so. This went on all June and July and August. The soldiers in the plain had reduced rations and the animals practically none.

But out of this chaos and potential disaster was born the great idea which developed to serve the Imphal Plain faithfully, and brought a vital line of communications- a line of life-blood to the cut-off Divisions- the Road from Imphal to Silchar. 1942 saw the initiation of three major road projects which were taken up by the British as a war effort in Manipur. First is the Tongjei Maril renovation and widening and the second is the cutting of a Jeepable track from Palel to Tamu. The third is the construction of Imphal-Tiddim Road. The first two projects took few months only. The Palel- Tamu track was cut by the tea Planters under the Indian Tea Association and the Tongjei Maril by the 82 Anti Tank Regiment Royal Artillery, both having no significant professional expertise in road making. The third Project took around one and half years to complete.

19th Century Tongjei Maril

In the early part of the 19th Century, the Bridle track between Bashkandi to Bishenpur was not fit for any ordinary soldier to march. During the seven years devastation, the Governor-General in council at Fort William decided upon the detachment of a large body of regular force under the direct command of Brigadier Shuldham to drive out the Burmese from Imphal. On 24th February 1825, the British forces under Shuldham arrived at Bashkandi. On 11 March 1825, Shuldham reported that “the state of the road is such that it is quite impossible to send supplies on to the advance, either on camels, bullocks, elephants or men”. It was extraordinary on the part of Gambhir Singh, to reach Imphal that June of 1825, in just 16 days from Bashkandi with 500 men and no resupply and bad weather.

As reported by Capt. R . Boileau Pemberton in 1835, there were three different routes that exist during the early 19th century by which the districts of Sylhet and Cachar are connected with Manipur.

“ Of the former, those most generally known and frequented are, that by Aquee, by which General Shuldham’s army intended to advance in 1825, the one by Kala naga, and a third, which has been but rarely resorted to, through the Khongjuee( Khongjai) or kokee (Kuki) villages. The point of departure for these, and every other known route, between Cachar and Muneepoor (Manipur), is Banskandee, a village nearly at the eastern extremity of the cleared plains, and where, by whichever route they might ultimately intend to advance, it would be necessary to form a depot for troops, military stores, and …..

The First or Aquee route, is the most northern of those mentioned and has been very little frequented since the Burmese war, its total length from Banskandee to Jaeenugur in the Muneepoor valley, is 86 and 5/8th miles, of which the first thirty passes through a dense forest, intersected by innumerable streams, scarcely exceeding in many instances six or eight yards in breadth, but which when swollen by rain are forded with extreme difficulty.

The Kala naga route, from Banskandee via Kowpoom( Khoupum), to Lumlangtong (present Bishenpur), is 82.5 miles, of which not more than 17 miles, or two easy marches, pass through the forest before mentioned, and in a part infinitely less intersected by streams and swamps, than that traversed by the more northern route of Aquee. This route has also the great advantage of crossing the Jeeree (Jiribam) at a point not more than eight miles distant from its mouth, up to which the Barak is navigable for boats of 500 maunds burthen….

On the Aquee route, there are but five ranges of hills crossed, and on that of Kala naga, eight, which would induce us to give the preference to the former, did not so considerable a portion of it pass through a low swampy tract of forest, extending from the Jeree river to Banskandee; and further east, a very serious objection is found in the fact of its passing over the bed of the Eyiee, a river which is liable to very sudden inundations from the number of feeders falling into it, and the vicinity of some very lofty and extensive ranges of mountains.

The third route, called the Khongjuee one, from its passing principally through the country inhabited by the tribe of that name, lies considerably to the southward of those already described; it commences at a ghaut on the great western bend of the Barak river, below the kookee( Kuki) or Khongjuee( Khongjai) village of Soomueeyol, and crossing the Barak on the eastern side of the same range of hills, passes over a tract of hilly country which attains less elevation than that across which the Kala naga and Aquee routes lie, and enters the Muneepoor( Manipur) valley at its south-western corner, three marches from the capital. The villages on this route are few and small, and as navigation of sixty-one miles from Banskandee must be effected up the Barak river before troops could enter upon the route, it is evidently wholly useless for military purposes”.

Early 20th Century Tongjei Maril

The early 20th-century map would show at 18 miles south-west of Imphal, a small village called Bishenpur, insignificant in itself but important in one respect. From it goes a bridle path meandering over mountains, across rivers, through jungles, up to dizzy heights, down to bamboo swamps: but ever-moving westwards until, after some 85 miles, it runs into Jirighat which is about 28 miles from Silchar, a railhead. This is the route described by Pemberton as ‘Kala naga’ route in 1835. The Kala naga route of Pemberton or the Imphal-Silchar bridle path of early 20th century can be understood as follows. Imphal to Bishenpur( 18 miles), Bishenpur to Leimatak river(13.25 miles), Leimatak river to Irang River through the Khopum valley ( 20 miles), Irang River to Barak Ahu river ( 24 miles), Barak Ahu river to Makru River ( 12 miles), Makru River to main Barak River ( 15 miles). After that, there were no rivers to cross and the path goes right to Lakhipur and Silchar.

The Work Begins

The 82nd Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery was raised in September 1941 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel G.P. Chapman DSO MC. It was formed by taking trained anti-tank batteries from existing units to be immediately available to go overseas. The nucleus came from the 57th ( East Surrey) Anti-Tank Regiment in Canterbury, which lost its Regimental Headquarters(RHQ) and one battery, 228. The other batteries were 205 from 52nd Anti-Tank regiment, 276 from 69th Anti-Tank regiment and 284 from 71st Anti-Tank regiment.

The Regiment mobilized at Butlins Holiday Camp, Clacton-on-Sea, then sailed in November from Liverpool in a convoy bound for the Middle East. Following Japan’s entry into the war, however, it was diverted to India. After a brief stop in Durban, South Africa, the regiment arrived at Bombay in January 1942. At the end of May, the regiment moved by rail with 23rd Indian Division to Assam on the eastern frontier of India. RHQ, 228 and 276 Batteries were employed in the Imphal area with troops at Imphal, Palel and Shenam. During this period, “Chapforce” formed from the regiment, undertook the construction of the road along the Silchar track, running west from Bishenpur to Lakhipur.

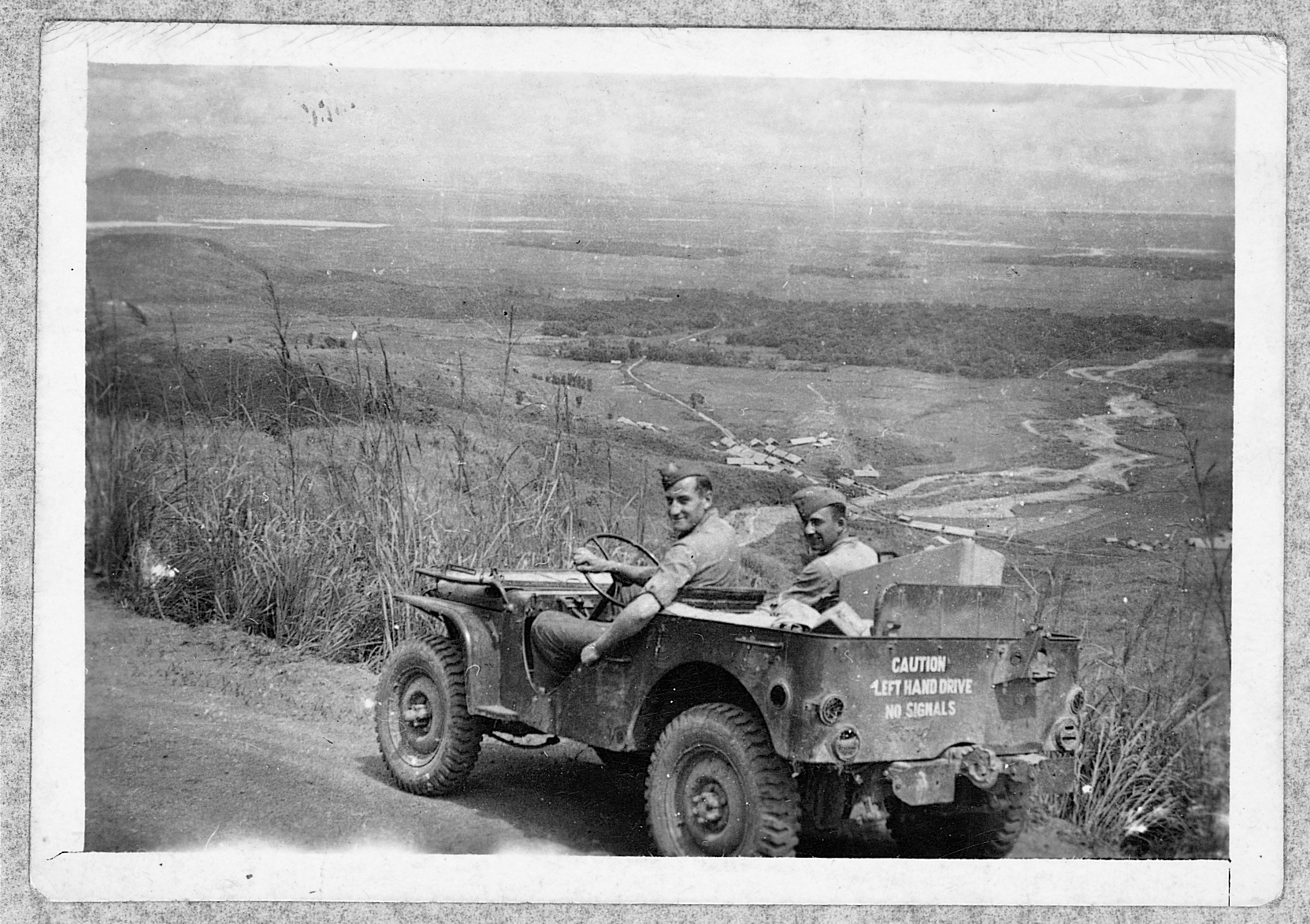

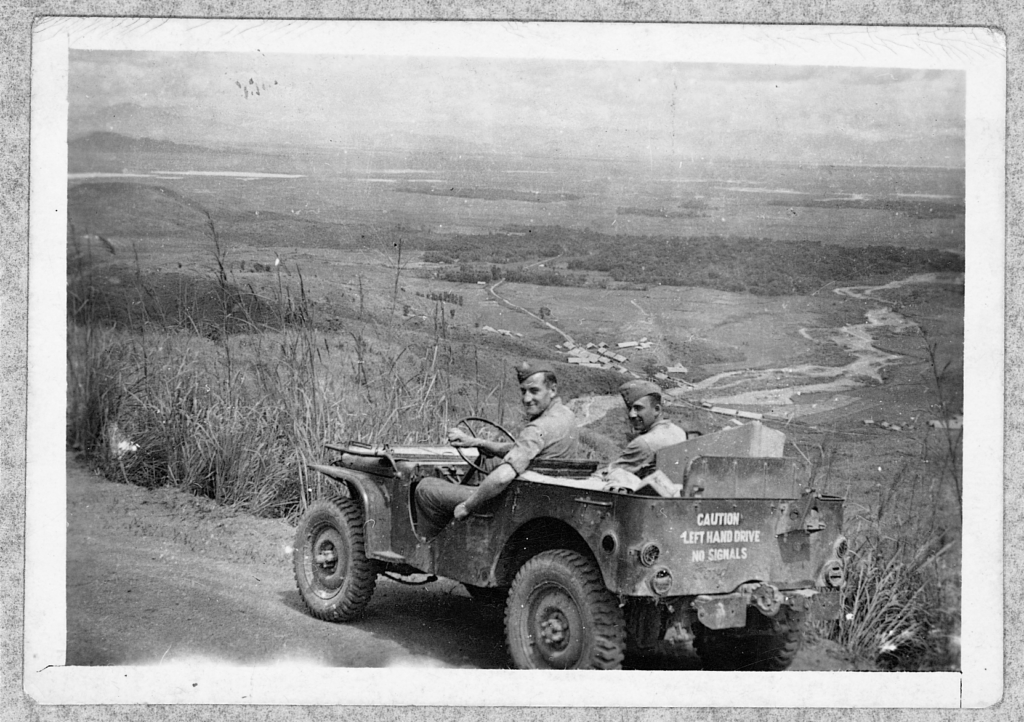

At a conference in Army Divisional H.Q. on 25th June 1942 the General gave Lt Col Chapman permission to send a party along the bridle track of Tongjei Maril to have a look at the Khopum valley, and if possible to push on to Silchar to see if it was possible to have pack mule or even country cart contact with Silchar. But after the conference, the B.G.S. ( Brigadier general Staff) of the Corps told Lt Col Chapman that reconnaissance had already been made and it was not worth starting out on another one! But he did it. And on the morning of 4th July, they started off. Young Harold West, the liaison officer, let the party which consisted of himself with sixteen British soldiers, nine Indian soldiers and twenty-one mules. Lt Col Chapman was attached to the party. With the party, they also had two Jeeps. Harold West went with the two borrowed jeeps just to help in the first stage with the baggage and so relieve the mules on the first climb of 3000 feet in 4 miles. One of them got three miles and then fell over the Khud 180 feet down with Sergeants Greenfield and Marner in it. Both soldiers were thrown clear in successive bounces and, although bruised, were all right. Much kit was lost, but four days afterwards the jeep was pulled up the 180 feet on to the track again. The second Jeep actually got four miles before it stuck- and there it remained for a fortnight. And one mule passed out from exhaustion; the effect of no rations but grass for weeks.

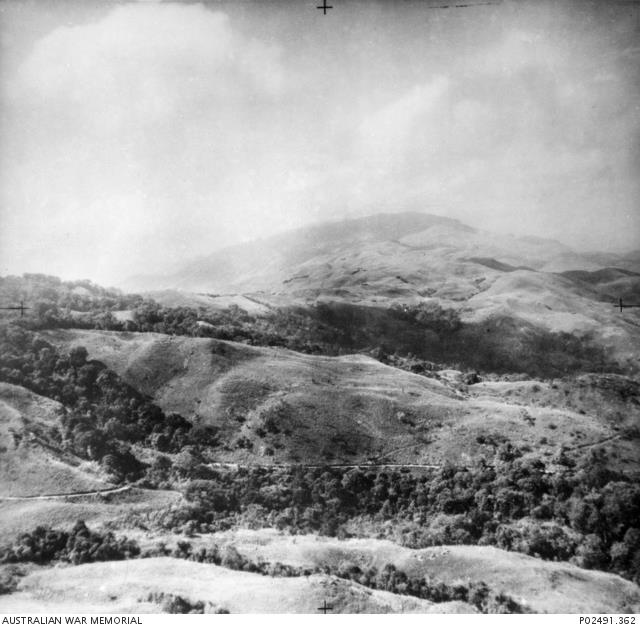

On 6th July, they started off again, making for the 40 milestones where there was reputed to be a Rest House, but which in fact had disappeared ten years before. Lt Col Chapman went ahead with Sergeant Botha and crossing the summit of the big hill at milestone 38, saw the most beautiful of all sight, their first glimpse of the Khopum valley. The team reaches Lagairong on 8th July. Upon return from Lagairong, Lt Col Chapman submitted a report asking for “100 soldiers and mentioned to make a Jeep track from Bishenpur to the Khopum valley in four weeks and through the valley to Lagairong in another three weeks”. The Army general told Lt Col Chapman to get on with it. The General mentioned he could not spare any soldiers, but Chapman could employ labours and get a move on.

On 14th July Lt Col Chapman sent Young to Bishenpur and Roger and Mossman to milestone 22 to recruit labour and established a base. They actually started work on that day, but it was not until the 19th July that fifty workers were employed, and the great effort had started.

The Progress

Each British other Rank (B.O.R) had a gang of labour which never exceeded 50 in number, except in the flat Khopum valley where they were under surveillance quite easily. It took two full months to make a road from Bishenpur to Milestone 23. Apart from being a very big climb, the track presented every known difficulty. Time and time again the made-up road was washed away before it had time to settle. Quagmires appeared all over the place. Long stretches of board road (Corduroy track) had to be made, hundreds of trees cut down, stone causeways over a mile in aggregate constructed, and still, it wasn’t a road. Long after other stretches, miles in advance had become first-class motor roads, the Bishenpur section offered resistance. Poor Young, who was commanding that section, had a horrible time. He grew thinner and paler every day and had a fever relapse in the middle of it all. But he was a dour Scot and he simply told Chapman that Bishenpur to the summit would become a road if it was the last thing he did on earth. Young got to like that shocking bit of road but was relieved when early in September, Chapman replaced him by James, and Young became the commander of the section Khopum Valley-Irang River ( M.S. 51) with headquarter at Lagairong.

Cambell established a forward H.Q at Tairenpokpi Rest House and was there with Mossman, who had taken over the road construction from the Summit to Tairenpokpi. This section, from milestone 23 to milestone 27, had been one of those which the Engineers had in mind when they declared the bridle path to be impracticable. And they were nearly right. Lightheartedly enough they undertook to make the road, but that section nearly brought them down. It took twenty-one precious days before it bore any semblance of being even a Jeep track, and not until the very end of September could one claim that it looked like a road.

(With permission by the Author from Ray Goodacre from http://57th67thanti-tank.co.uk)

Somewhere about the 24th milestone, there was a wall of rock that confronted the Chapforce. The solid mountain of rock along which the track narrowed to 2’9” for a distance of 30 yards became known as Botha’s Slide. Four solid weeks it took them to blast out Botha’s Slide, and during that period they shifted 760 tons of rock. The C.R.E( Commander Royal Engineers) was magnificent. He didn’t know that they were using up his gelignite at an alarming rate. He never questioned it. Chapman wrote that the C.R.E helped them tremendously.

River station was established at Leimatak River( M.S 31.25) and on 3rd August, Brown went through with Sergeant Martin and nine men to tackle the difficult stretch up to Milestone 38, a climb of some 3000 feet in seven miles. And closely on his heels went Harold West on 5th August with orders to start at Milestone 38 and smash through to the Khopum Valley( M.S 43) in twelve days. With West went Sergeant Johnson, a very capable man and a certainly for the job of punching through. All this was happening whilst Chapman was battling with Botha’s Slide and the rock fields in the Tairenpokpi area. Brown has a tough job; there was no village near the river, so he had no labours. But Brown and his chaps didn’t seem to care: they pushed off into the rising jungle to make their jeep track, out of touch with Chapman except by native runner. And they did produce a track.

On 20th August came the electric news that Sergeant Johnson had broken through to the valley; this coinciding with Brown reaching M.S 38. They had bettered the promised time by five days, and now Brown and West Parties could rush off right forward to start working back towards Chapman. The General was delighted. Apart from the fact that they had kept faith on time, there was then communication with Khopum valley, and in a few more miles the job would be half over.

At this stage, the plan for the final assault was formulated. Bannister was to go to the very end at Jirighat and work back, with faithful Sergeant Botha as his second-in-command. Harold West from Oinamlong was to work east and west to join Brown and Bannister respectively, and Brown, from Nungba, was also to work east and west to join Young and West respectively. And so it worked out.

There was a problem how to traverse the three miles off of squashy mud along the floor of the Khopum valley and make it fit for motor transport. At the far end of the valley, there were Pawchunglung, the headman of Lagairong, and Akumba, the headman of the important village of Khopum. Upon the two men, the British urged the need for labours and more labours, and in the end, they produced over 250. These men, under the guidance of Langton and Vinson, raised the track nearly three feet-for the whole length of the Valley M.S. 43 to M.S. 46.5- and drained the original mud track off into water channels. The whole job took three weeks and was a magnificent example of determination.

Harold West in his section was more ambitious. He started off moving west from M.S 80 and made two miles of Brooklands track before he was stopped and turned east to make first a Jeep track down to Barak River. He did it all right, and then backs to his first love- his beloved road to the west, to the Makru River, to link up with Bannister.

Campbell detailed the finishing touches on West’s job when he went through. Much was to be done, and he sends Chapman very full report. West should have been the first to bring his section to a finish because it was the shortest. West’s party says it will be the best, although they have taken much longer.

Brown, the most reliable young man, had the worst job. He went off to Nungba, and very soon had a jeep track to ride on from the Irang River at M.S. 51 up to the Rest House at M.S. 63. It was a shocker, rocks, poor bridges; narrow over 300 feet khuds-all the fun of the fair.

As the pace gets hotter, Chapman sends Roger, the Signals Officer, over Brown’s head at M.S. 69, at Kambiron, to build a road from there to the Barak at M.S 76 to join with Harold West.

The Local tribes’ Participation

The villagers were recruited as labours. The village headman contributed to whatever they can in terms of food, labour and service. Lt Col Chapman had high regard for the local tribesmen, he wrote that “the best way to get them (tribes) on the job is to show them a model of the road made out of mud and sticks. Once they grasp the idea they are off, diving into the jungle for timber, digging for stones and rocks, and the work has begun. They think nothing of walking five miles to report, then four or five to the job, and returning in the evening tired out, but still cheerful. Always they tell you they want to work for the Sirkar and those they are loyal men. And work they do, all for the sum of one rupee a day with an occasional handful of salt”.

Once a headman asked Chapman if he could send the women and children to look at the white soldiers” the like of which they have never seen”. An hour later on all sides could be seen faces peeping out of the jungle watching every movement of the soldiers- and within a few hours of that, the women and children were drawing water for them, and later still working on the road in hundreds. The Chapangs or children work like anything, clearing stones and grass for some nine or ten hours a day all for four Annas. If they are half-grown and really work hard, they can earn up to eight annas. Each night, after the paytable, came the hurts and the ills. The locals came miles for medicine; they had Gangrene sores, masses of horridly septic jungle sores, ugly cuts, an occasional snake bite, and dozens of malarial spleens, coughs, colds and belly-aches. All to be cure by the white man’s medicine.

Chapman wrote that “all of them are very honest-anything left about on the road is brought in at once. No man ever claims more than his just wage. In this respect, they are a revelation. If a labour shortage threatens, tell them that those who work the next day will get a handful of salt and hear the music. Music is a gramophone, which is an abiding wonder and joy to them. They will sit around until long after dark, forgetful of food and home alike, listening to the gramophone. They sigh like children after each record and palpitate with excitement when they see another being prepared. Best of all they like a song with a woman’s voice.”

The old Soldiers fought the Last battle

Seven days to go before the road is open to moving troops. Can it possibly be done? Mathematically it is impossible; a Jeep track yes, it already exists; but a finished road, no. On the night of 23rd September, there remained nineteen miles of track to be converted, in areas where the total number of soldiers on the Road was thirty –three. Could thirty-three men do roughly one thousand yards each in a week? There were rock fields and narrow track; a few awkward bridges and a collapsed causeway were left to be done with.

Whom can they bring forward to help? Young and his team at Lagairong are the only answer, therefore he was told to close his work in four days and advance to M.S 59 to work from there up to M.S 61, and down to M.S 56. North and south went the interpreters with the message that one more week’s work would finish the “Lampi”. Colonel Sahib was calling them to help in that last effort. Would they come? They did. From all the affected areas came reports: thirty men arrived today, ten men are coming tomorrow, and so on. Old Soldiers from the last war ( 1st World War) turned up leading in their friends. They produced certificates saying that they had served in France, and were exempt from the Hut Tax for life- but they were willing to help on the “Lampi”. Nagas and Kukis alike came in. A large number of Kukis served in France during the First World War and many old veterans came out to cut the rocks. Mentioned can be made of the grand old chief, Nungkhogin a well-dignified chief of Village Sungsang, who came to help the Chapforce with his family and villagers. He had credentials from the highest in the land for his work in France, his loyalty and his ability as a headman. Another story of a veteran from the First World War, who wore Medal Ribbons, with white-headed and bend came and meet Chapman. He brought thirty men and said he wants to work on the road and he will do it until he drops.

Officers and men who actually worked on the road full time are listed below:-

| 1 | Major J.A Cambell, R.A | 26 | Gnr. Fry. G |

| 2 | Lieut. P.S. James, R.A | 27 | Gnr. Bell . J. |

| 3 | 2/Lieut. J.H. West, R.A. | 28 | Gnr. Twist. J |

| 4 | 2/Lieut. R.L. Brown, R.A | 29 | Gnr. Brook. H |

| 5 | 2/Lieut. A. Young, R.A. | 30 | Gnr. Lowther . J |

| 6 | R. S. M. Thomas. G. | 31 | Gnr. Stobart .D |

| 7 | Sgt. Watson. P | 32 | Dvr. Stubbington. E. |

| 8 | Sgt. Carberry. F | 33 | Dvr. Barnes. F |

| 9 | Sgt. Martin. E | 34 | Dvr. Braggington. A |

| 10 | Sgt. Espey. J | 35 | Gnr. Holdernesse. W |

| 11 | L/Sgt. Johnson. R | 36 | Dvr. Mather. F |

| 12 | L/Sgt. Botha. F | 37 | Dvr. Moody. E |

| 13 | L/Sgt. Marner. T | 38 | Gnr. Watkins. L |

| 14 | L/Sgt. Akers. S | 39 | Dvr. Wheeler. G |

| 15 | Bdr. Blevins. J | 40 | Gnr. Buxton. M |

| 16 | Bdr. Thirkle . H | 41 | Dvr. Heath . G |

| 17 | Bdr. Boyle. F | 42 | Dvr. Vinson. T |

| 18 | Bdr. Tompkinson. G | 43 | Dvr. Baldwin. V |

| 19 | L/Bdr. Morge. W | 44 | Dvr. Smith. H |

| 20 | L/Bdr. Prince. H | 45 | Dvr. Veness . F |

| 21 | L/Bdr. Langton. J | 46 | Dvr . Johnson. S |

| 22 | L/Bdr. Wiltshire. F | 47 | Sigmn. Naylor. V |

| 23 | L/Bdr. Jenkins. M | 48 | Dvr. Gilmore. G |

| 24 | L/Bdr. Slade. S | 49 | Sigmn. Mycock. C |

| 25 | Gnr. Tree. D | 50 | Gnr. Lewis. R |

Bridging Party

The rivers run north and south and each river has its suspension bridge running east and west. There were seven in all on the road, varying in length from about 150 yards to 50 yards. The suspension bridges were a real nuisance. They were old and obviously unreliable, and wedging a jeep across was always a gamble- would it collapse or not? And much time was lost transshipping from Jeep to Jeep across the bridges. All the bridges were widen and renovated.

The party consisting of the below-mentioned personals worked on the Road for a forthnight, by themselves, on a particular job involving the construction of four bridges.

- B.S.M . Duke. R

- Sgt. Parr. A

- Sgt. Fuller . C.

- Sgt. Bitthell. F

- Sgt. Hopkins. E

- Sgt. Daughtrey. E

- Gnr. Mallett. F

- Gnr. Jobson. E

- Gnr . Miller. A

- Gnr. Minett. A

- Gnr. Smith. R

- Gnr. Smith. W.

The Road was Open

During the tenure of the work, many men from Chapforce suffered from jungle sores. Bannister, Veness, Derbyshire and Sergeant Carberry were hospitalized. Road accidents happen more often than not while the Chapforce was working for the stipulated time. Many a time the Jeep fell many feet down the khud injuring many soldiers.

On 30th September the first reconnaissance party of the soldiers who were to use the road left from Nungba. A few days back Chapman had sent a party through from Bishenpur to Silchar in one day- a distance of 109 miles. During those days, Calcutta was another day from Silchar, a contrast with the Dimapur Road method- anything from four to ten days!

Many of these men and officers from the Chapforce never made to their home. After the work at Tongjei Maril, they were deployed for cutting of Imphal-Tiddim road and many perish during the fight with the Japanese force. Today many of the soldiers mentioned in this article are interred at Imphal War Cemetery.

Conclusion

The main reason for the renovation and expansion of the road was to create an additional route for the supply of goods to the British Army garrisons and depots in Imphal. This route was also to help assist the returning British allied troops who were returning to India after the fall of Burma to the Japanese.

To raise, organize, direct, move and maintain labour force against every difficulty of climate and terrain was a magnificent achievement of the 82nd Anti Tank regiment under Lt Col G.P Chapman. It was only made possible by the high efficiency of the man leading it. The road from Bishenpur to Lakhipur, a distance of 109 miles was built between the dates 19th July and 29st September 1942 by Chapforce.

In September 1942, G.P.Chapman wrote, “ It did happen, and very quickly; the Khopum Valley today echoes the noise of passing motors. Purists may call it a desecration of wild places. Economists say it is promising. Soldiers call it making good the flanks, and I call it still further proof of what the Royal Regiment can do. And the Nagas? What they call it I don’t know, except the Lampi. They are funny little men, but after all, they did build the Road”.

(Yumnam Rajeshwor Singh is the Co-Founder of 2nd World War Imphal Campaign Foundation)

Bibliography

- Capt. R. Boileau Pemberton, Report on the Eastern Frontier of British India, 1835, Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta

- Louis Allen, Burma The Longest War,1984, Phoenix press, London.

- Lt. Col G.P. Chapman, The Lampi, 1944, Thacker Spink & Co Ltd, Calcutta.

- Laldena, History of Modern Manipur, 2012, Reliable Books Centre, Imphal