Another chapter of oppression gets closure as the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) has once again taken centre stage in Indian politics with its implementation ahead of the Lok Sabha elections. The act is an act of delicate balance between humanitarian considerations and constitutional principles

KRC TIMES Desk

KRC TIMES Desk

Another chapter of oppression gets closure as the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) has once again taken centre stage in Indian politics with its implementation ahead of the Lok Sabha elections. The act is an act of delicate balance between humanitarian considerations and constitutional principles. At its core, the CAA aims to provide citizenship to undocumented non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan who have faced persecution in their home countries. By granting Indian nationality to persecuted minorities such as Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Parsis, and Christians, the Government seeks to fulfil its commitment to safeguarding the rights of those fleeing religious persecution.

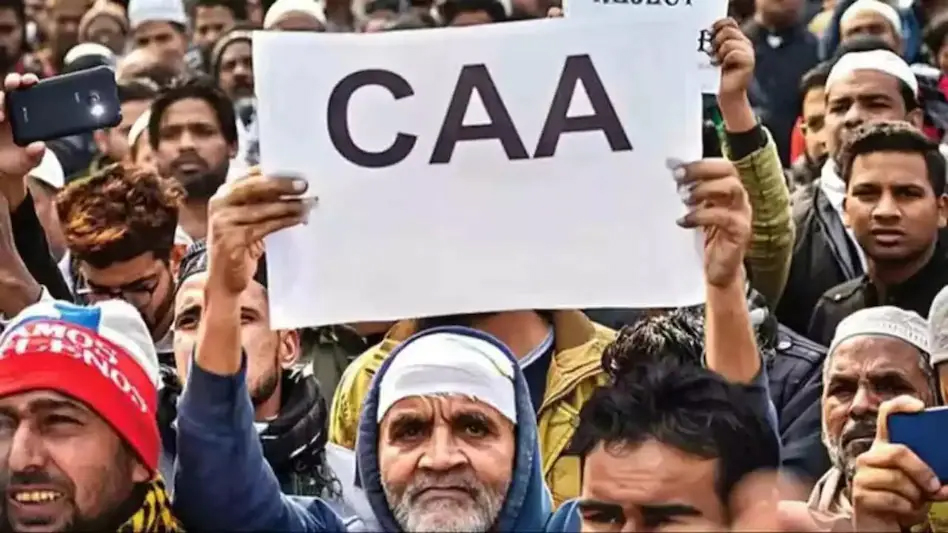

However, the implementation of the CAA has not been without its challenges. Since its passage in December 2019, the law has faced significant opposition, leading to protests and the loss of lives. The protests highlight the deep-rooted concerns regarding communal harmony and the protection of minority rights in India. The timing of the implementation of the CAA, just ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, adds another layer of complexity to an already contentious issue. While the ruling party sees it as a fulfilment of its electoral promise and a demonstration of its commitment to the welfare of persecuted minorities, the opposition views it as a political manoeuvre aimed at consolidating votes.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act eliminates legal obstacles to resettlement and citizenship, providing a pathway to a dignified life for refugees who have endured decades of hardship. According to officials, obtaining citizenship will safeguard their cultural, linguistic, and social heritage while also guaranteeing economic opportunities, freedom of movement, and property ownership rights. For the critics of the CAA, the principle of equality does not mandate that every law must apply universally. It acknowledges the state’s authority to establish classifications as long as they treat members of a defined group equally. Thus, a law catering to a specific class cannot be accused of denying equal protection merely because it does not extend to other individuals. The Supreme Court has consistently emphasised that it cannot intervene solely because alternative methods exist, leaving the determination of the most suitable scheme to the Government’s discretion.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Act aims to grant Indian citizenship to minority community members from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who face persecution in their respective countries. It is evident that minorities in these Islamic nations endure oppression, a fact not in need of further proof. Criticising Parliament for concluding the necessity of safeguarding these minorities would be unwarranted. Furthermore, it’s crucial to recognise that classification based on religion is not inherently unconstitutional, especially considering our Constitution’s provisions for protecting minority religious communities. If the law allowed migration for all religious groups from the mentioned countries, it would essentially dissolve our borders.

Practically, the implementation of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, presents an opportunity to stand up for persecuted minorities and provide them with much-needed support. The Government will have to navigate this complex terrain with sensitivity and foresight, ensuring that the rights and dignity of all individuals are safeguarded. Its implementation is going to change the lives of thousands who have faced decades of oppression.